Seismology

This Mw 7.8 earthquake was a complex sequence of fault ruptures. It included 12 major faults and at least nine lesser faults. The initial rupture started on a fault near the rural townships of Waiau and Rotherham. Ruptures then jumped from fault to fault as it moved at a speed of almost 2 kilometres per second. The ruptures travelled 170 kilometres along the South Island’s north-east coast. Seismic energy was released for nearly 2 minutes. Scientists have recorded more than 16,000 aftershocks in the 6 months following the event.

Damage

The earthquake caused a lot of damage to homes, businesses, primary industry, and infrastructure, which has disrupted the lives of many. There have been different effects for small rural communities compared to the larger towns like Kaikōura.

There were two fatalities, and many people were injured. The earthquake struck just after midnight when popular tourist destinations were deserted at the time. This was fortunate, as the Ohau Point seal colony, for example, was covered in a landslide.

Homes were damaged, and some businesses closed. Farms were left with land damage and reduced access to markets for their goods (see Communities Adapting to Change). Farms in Hurunui had land damage from the earthquake in addition to damage from years of drought. Communities suffered with the loss of trade from passing traffic and tourists.

State Highway 1 and the KiwiRail Main North Line between Picton and Christchurch were significantly damaged. Coastal uplift changed both the coastline and the seafloor. Disruption from the earthquake was not limited to the Hurunui, Kaikōura and Marlborough areas. Buildings in Wellington and Lower Hutt were also damaged. A number of these were demolished as a result.

Tsunamis

The tide and tsunami gauge near Kaikōura measured a 2.5 metre drop in water level 25 minutes after the earthquake. This suggested a possible tsunami. The water level then rose about 4 metres from its lowest point, and a series of waves continued for several hours.

Scientists also measured the height of the tsunami using onshore debris. Goose Bay showed the highest run-up height of 6–7 metres. In Little Pigeon Bay on Banks Peninsula, the tsunami wave was enhanced by the shape of the bay. The wave flooded a cottage causing a large amount of damage.

Landslides

The earthquake produced more than 10,000 landslides across the region. They caused major damage and disruption to a large area. Many debris dams were also created. At least 50 of these dams contained over 1 million cubic metres of rock each.

The 8 largest landslides had volumes of over 5 million cubic metres each. The largest of these was the Hapuku River dam with around 20 million cubic metres. Heavy rains and erosion over time caused many of the dams to breach.

Geologically active area

Plate boundaries

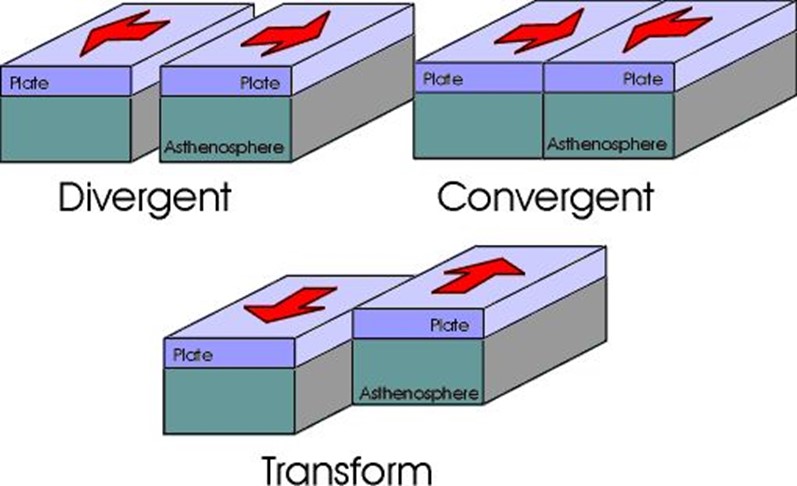

There are three types of tectonic plate boundaries. They are characterised by the way the plates move in relation to each other. The movement of these plate boundaries cause different things to happen on the Earth’s surface.

- transform boundaries - where plates slide past each other.

- divergent boundaries - where two plates slide apart from each other.

- convergent boundaries - where plates slide towards each other.

The November 2016 earthquake occurred on the tectonic plate boundary between the Australian and Pacific plates. This seismically active area originally created the Southern Alps and the Kaikōura Ranges.

The Alpine Fault – where the plates meet and slide horizontally past each other – is to the south of where the ruptures occurred. The Hikurangi subduction zone – where the Pacific plate moves under the Australian plate – is to the north. The regions of Hurunui, Kaikōura and Marlborough, being between these two quite different types of boundaries, therefore experience both sideways movement and plates pushing up against each other, making it a very seismically active area.

The two tectonic plates of the Australian and Pacific plates push past each other along the Alpine Fault. Image: GNS Science.

Moving the land in many directions

Ground shaking from this earthquake was the most forceful ever recorded in New Zealand. As a result, the landscape was significantly altered. GNS Science reports that the earthquake:

- pushed the rocky seabed up by as much as 6.5 metres. This formed a vertical barrier between the shore and the sea in some places

- moved the land from Kaikōura to Cape Campbell north-west and closer to the North Island. The largest movement recorded along part of the Kekerengu fault was nearly 12 metres horizontally

- raised some parts of the inland region by up to eight metres.